Analyzing the Federalist Papers

Secondary American History (Python)

In this activity, we will analyze the federalist papers and predict their authorship by calculating a score.

Activity

The Federalist Papers are a series of articles written by three of the Founding Fathers (James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay) during the adoption period of the United States Constitution. They used a pseudonum known as “Publius” to maintain anonymity. Often, it is important to maintain anonymity for one’s own safety, to avoid persecution resulting from one’s speech; other times, anonymity allows one to avoid revealing their own beliefs in their writing. But if you’ve ever read e-mails or text messages from your friends, you have probably found that you can guess who wrote something before you even see the person’s name. That’s because we have unique writing styles that can help identify an author over time. Sure enough, some of the previously unknown authors of the Federalist Papers were identified through stylometry (the study of one’s linguistic style). Today, we will write a program to do just this.

Stylometric Features

Before we begin, brainstorm in groups the types of things you might look for when guessing who wrote an e-mail, text message, or paper. What kinds of things do we do that are unique - for example, does somebody write long sentences or use bigger words? What could help you make a better guess?

Our approach will be to read a lot of examples of writing from each author, and then comparing their style to the style of the unknown paper. Whoever best matches that style will be our guess.

Making a Plan

The first step to writing any program is making a plan. We want to break the problem down into small steps that are easier for us to manage, and then tackle those steps one-by-one. Here’s what we’ll do:

- Read all of the Federalist Papers and group them by their author

- For each author, scan through their papers and count how many times they use each word (this is called the word frequency)

- We’ll pick one of the Federalist Papers and pretend that we don’t know who wrote it. Then, we’ll compute its word frequency and compare it to the three potential authors that we know about. Whichever author has the most similar word frequency will be our prediction.

- As a bonus, we’ll make a bar graph of the top 10 most common words for each author.

As you can see, each of these steps would be quite labor intensive to do by hand! Using a computer program, we’ll automate this process so that we can do this much more quickly and easily.

The Program

It is helpful to think of these steps as "functions", so that we can describe how each step works in isolation from the others. That way, we can focus on each step of the process, one at a time.

Step 1: Reading the Federalist Papers

We will read the Federalist Papers from the Internet. They are available at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1404/pg1404.txt. Python provides a library called urllib that can read data from the web. Here is a function to do just that, returning the result as plain text (called utf-8) that we can read later.

def read_web(url):

page = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

data = page.read()

page.close()

return data.decode("utf-8")

Now, we can turn our attention to grouping the papers by their author. We want to put each of the 85 Federalist Papers into three piles: one pile for each of the three authors. That way, we can analyze the linguistic style of the papers written by each author. We’ll begin by calling the read_web function we just wrote and providing it with the URL of the Federalist Papers we saw earlier. That provides us with a variable with all the text of the Federalist Papers inside.

def read_federalist_papers():

allfeds = read_web("https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1404/pg1404.txt")

Next, we will create an array of these papers, pull out the text of just that paper, and find its author. That sounds like a lot of work, so let’s pretend we have a function to do it. We’ll call it get_federalist_paper and it will take in the whole body of Federalist Papers, and the number of the paper we want back. In response, this magic function can give us the text of the paper and the author that wrote it.

If we had that function, we could call it on paper 1, 2, 3, all the way up to 85. The range(a, b) function gives us the set of all numbers from a to b-1, so this array and loop will look like this:

feds = []

for i in range(1, 86):

author, text = get_federalist_paper(allfeds, i)

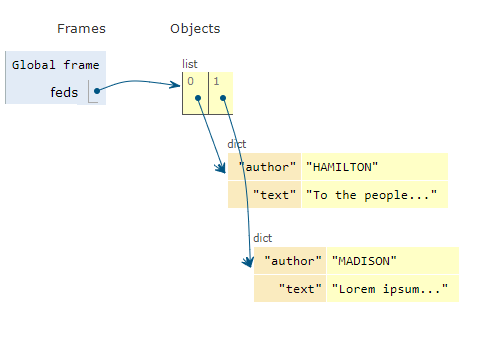

Finally, we can create a dict structure, which is kind of like an array, but allows us to tag elements of a single variable. So we can group the author and the text together into a single variable. Dictionaries in Python are declared with the dict() or {} notation. We’ll add each paper and author to our array of individual Federalist Papers, and return that array of dictionaries:

fed = {}

fed['author'] = author

fed['text'] = text

feds.append(fed)

return feds

Our array will look something like this (figure generated at https://pythontutor.com/):

Writing that Magic Function

Earlier, we relied on a "magic function" to ease our workload. This function was to take in the Federalist Papers text, and the paper number we want, and then find and return the text of that paper along with the author. Let’s call that function get_federalist_paper, and set up variables to hold the text of the paper and the author (the two items we promised to return):

def get_federalist_paper(allfeds, fedno):

data = ""

author = ""

If we look at the text of the Federalist Papers document we downloaded, you’ll see that each paper begin with the line FEDERALIST No. 1 (or whatever number). We can use this to extract the paper we want. If we want paper 5, we can pull all the text from FEDERALIST No. 5 up to FEDERALIST No. 6. Let’s look for those two strings of text:

startno = "FEDERALIST No. " + str(fedno)

endno = "FEDERALIST No. " + str(fedno+1)

start = allfeds.find(startno)

end = allfeds.find(endno)

If we can’t find the beginning of the paper, it probably doesn’t exist, so we’ll just return nothing. The find function returns -1 if it can’t find the text we’re looking for:

# Paper not found?

if start == -1:

return data

There is the question of what to do if we can’t find the beginning of the next paper, though. When can that happen? If we’re looking for the last paper, there won’t be a "start of the next one" - so we can read until the end of the file in that case. Do you think you might have missed that detail? This is why it’s so important to test programs using lots of possibilities; try to think of the ways you can break the program, and make sure it works. Try getting the first paper, the second paper, the last paper, a paper that doesn’t exist, and so on. This is what software testers do! They get to think like a contrarian to help make software more robust.

If we can’t find the end paper, let’s look for the ending text: scrolling to the bottom, it looks like this line marks the end: *** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FEDERALIST PAPERS ***.

# Find the end of the paper, or the end marker of the last paper, or the end of the file

if end == -1:

end = allfeds.find("*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FEDERALIST PAPERS ***")

if end == -1:

end = len(allfeds)

To help avoid biasing our analysis, let’s remove some of the boilerplate text (like FEDERALIST No. 1, by moving our starting position beyond it:

# Remove the starting number

start = start + len("FEDERALIST No. " + str(fedno))

Now, let’s get just the text in between these two markers. Python gives us a nice way to do this, by specifying the starting and ending position of the text that we want to extract:

data = allfeds[start:end]

Similarly, let’s strip out text like “PUBLIUS” and the author’s names, since they’re not really intended to be in the text we’re analyzing. Before we do that, let’s find the author’s name in the document, and save that so that we can return the author’s identity.

# Stop at the signature at the end ("PUBLIUS"), if present

publiuslocation = data.find("PUBLIUS")

if publiuslocation > -1:

data = data[:publiuslocation]

# Get correct author

if "MADISON, with HAMILTON" in data:

author = "MADISON, HAMILTON"

elif "MADISON" in data:

author = "MADISON"

elif "HAMILTON" in data:

author = "HAMILTON"

elif "JAY" in data:

author = "JAY"

# Remove authors

data = data.replace("MADISON", "").replace("JAY", "").replace("HAMILTON", "").replace("MADISON, with HAMILTON", "")

data = data.strip() # remove leading/trailing whitespace

return author, data

Sometimes, two authors wrote a federalist paper, if you notice that in the code above. We’ll put them into their own dictionary "bucket".

Step 2: Calculating the Word Frequency for Each Author

Let’s make another dictionary, with one entry for each author, and loop over the array of Federalist Paper dictionaries we just created:

word_counts = {}

word_counts["JAY"] = None

word_counts["HAMILTON"] = None

word_counts["MADISON"] = None

word_counts["MADISON, HAMILTON"] = None

for i in range(len(feds)):

fed = feds[i]

author = fed["author"]

text = fed["text"]

Now, we’re ready to count the words. Let’s make another magic function for that so we can come back to it later:

word_counts[author] = count_words_fast(text, word_counts=word_counts[author], minlen=MINLEN)

The website https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/text-analysis-in-python-3/ provides a nice article on a method to read text and quickly count the word frequency inside. We’ll adapt this approach and cite it accordingly:

# https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/text-analysis-in-python-3/

def count_words_fast(text, word_counts=None, minlen=None):

text = text.lower()

skips = [".", ", ", ":", ";", "'", '"', "-", "?", "!", "\r\n", "\r", "\n"]

for ch in skips:

text = text.replace(ch, " ")

text = text.strip()

input = text.split(" ")

# remove small words

if not (minlen is None):

input = [x for x in input if len(x) >= minlen]

# Create the Counter the first time, and update it the second time

if word_counts is None:

word_counts = Counter(input)

else:

word_counts.update(input)

return word_counts

This function returns a python Counter variable, which is exactly the frequency analysis we need. Think of this like a dictionary, where each element (key) is a word, and the value is the number of times the author used that word in this text. I’ve modified the function in the article to create the Counter the first time we provide it with a paper to count, and to update the count every other time. That way, we keep a running total of all the words that each author uses across all of their papers. In other words, we don’t want 85 word counts (one for each paper), but rather 3 (one for each author, with the total word counts over all their papers).

I’ve also modified this program to only count words that are greater than a certain length (say, 5 letters). Why might it be helpful to exclude short words when learning the linguistic style of the authors?

Step 3: Predicting the Author

Finally, we can predict the author of a paper. We’ll write a function called predict_author to do the work for us: it will take in the set of papers, the set of counts for our authors, and the paper we want to analyze. It will return the name of the author that actually wrote the paper, and our predicted author. To test things out, we’ll call this function on every paper using a loop. Finally, we’ll print out the prediction and the actual answer (known as the ground truth), to see how we do.

for i in range(len(feds)):

# i+1 because element 0 of the array is Federalist Paper 1

predicted, actual = predict_author(feds, word_counts, i+1)

print("FEDERALIST No. {} was written by {}, and I predicted {}".format(str(i+1), actual, predicted))

Now, let’s fill in this function. We know we want to return the prediction, and we know from our earlier work who wrote each article (the actual author), so we’ll set up our parameter inputs and results as a first step:

def predict_author(feds, word_counts, fedno):

predicted = ""

text = feds[fedno-1]['text']

actual = feds[fedno-1]['author']

Now, let’s do the same work we did with each Federalist Paper when we learned about each author’s word counts. This time, we just don’t know which author to attribute the paper to. We can count the word frequency in this paper:

counts = count_words_fast(text, minlen=MINLEN)

The final step is to decide which of the three authors has a word frequency that is most similar to this unknown paper’s word frequency. There are many ways to do this, as you saw at the beginning. Should we see how long each author’s words and sentences are? Should we look for compound sentences, or certain word styles? These ideas are called features, and we can use one or more of them to help us decide. Either way, we’ll compute a number that specifies how similar each author’s style is to the unknown paper, and we’ll select the author with the highest score as our prediction. It’s important that we select an idea that gives a valid score - one that we can use to correctly predict the author. For this example, I’m going to look at the rank of each author’s word frequency. So, if Alexander Hamilton uses the word "country" most often in his works, and the word "country" appears as the second-most used word in this unknown paper, that’s a good indicator. We’ll subtract rank 2 from rank 1 and add it to Hamilton’s score for that paper. We’ll do that for the top N words for each author, and compare their scores.

we’ll write a placeholder function compute_score to do this for us:

scores = {}

for author in ["JAY", "MADISON", "HAMILTON"]:

score = compute_score(counts, word_counts[author])

scores[author] = score

# highest score wins

predicted = max(scores, key=scores.get)

return predicted, actual

The compute_score function looks at the rank difference feature for the most common N words by each author. Whoever has the lowest total rank difference wins. We’ll begin by getting the most common 100000 words (which is probably all of them!), sorted by most common to least common, using a function called most_common. We’ll separate them into their individual words and frequencies using the zip function.

def compute_score(textcount, corpuscount, words=100000):

textcommon = textcount.most_common(words)

corpuscommon = corpuscount.most_common(words)

items, freqs = zip(*textcommon)

corpusitems, corpusfreqs = zip(*corpuscommon)

Now, let’s compute the score. We’ll start with a score of 0, and add the difference in rank for each of the author’s words and the rank that the word appears in the paper. We’ll take the absolute value of this difference so that negataive numbers don’t reduce the score (after all, they’re differences too!):

score = 0

for i in range(len(items)):

word = items[i]

if word in corpusitems:

corpusidx = corpusitems.index(word)

else:

corpusidx = words # max score

diff = abs(i - corpusidx)

score = score + diff

In this case, a higher score is actually worse: it means that their ranks were more different. That’s no problem: we could always take the lowest score as the winner, like in the game of golf. But I like high scores to win, so how can we turn a large number into a small number? We’ll take the algebraic inverse (for example: score = 1 / total).

# make higher scores represent better quality predictions by taking the inverse of the difference of the ranks

return 1.0 / score

Step 4: Visualizing the Word Frequencies

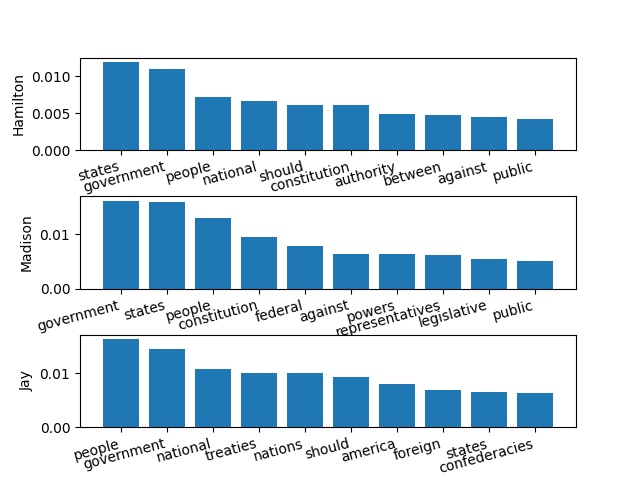

For fun, we can create a bar chart of each author’s top 10 word frequencies. Here is a function to do this, and the resulting output:

def plot_counts(word_counts):

fig, ((ax0, ax1, ax2)) = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols=1)

hamilton_labels, hamilton_values = zip(*(word_counts["HAMILTON"]).most_common(10))

madison_labels, madison_values = zip(*(word_counts["MADISON"]).most_common(10))

jay_labels, jay_values = zip(*(word_counts["JAY"]).most_common(10))

ax0.bar(hamilton_labels, hamilton_values)

ax0.set_ylabel("Hamilton")

ax1.bar(madison_labels, madison_values)

ax1.set_ylabel("Madison")

ax2.bar(jay_labels, jay_values)

ax2.set_ylabel("Jay")

plt.setp(ax0.get_xticklabels(), rotation=15, horizontalalignment='right')

plt.setp(ax1.get_xticklabels(), rotation=15, horizontalalignment='right')

plt.setp(ax2.get_xticklabels(), rotation=15, horizontalalignment='right')

fig.subplots_adjust(hspace=.5)

plt.show()

What do you notice about the writing style of each author, and what might it say about their worldview?

The Finished Project

Here’s my finished product, available at https://replit.com/@BillJr99/FederalistPapers:

Follow-Up

Scrutinizing the Training Approach

You might have noticed that we cheated here a little. We used the Federalist Papers to learn the writing style of the authors, and then applied that style to the unknown paper! This is a common danger with machine learning algorithms: using the training data to learn about the writing styles, and then applying it to itself. What can we do about this? There are at least two possibilities:

- Pretend we don’t know the authorship of any of the Federalist Papers, and learn the writing style of the potential authors through other essays

- Remove the unknown paper from the training set

How might you modify this program to implement the second idea?

Accuracy Rate

Modify the program to compute the percentage of predictions that were correct.

Implications of Writing Style

In historical context, can you infer who had more common values from their word frequencies? For example, which of the authors likely favored State powers over Federal powers, and vice-versa? Sometimes, it was determined that two of the authors co-wrote some of the Federalist Papers. From their most common word frequencies, can you guess which two likely collaborated on these?