Telling Time with WWVB

Secondary Computing (Python)

In this activity, we will listen to a data broadcast of the current time using the WWVB radio station, and learn about radio modulation to send data around the world.

Activity

Getting Started

Imagine you wanted to send some information “over the air” to a classmate across the room. Radio waves are a form of light at frequencies that we can’t see. So let’s use a flashlight. You can turn the flashlight on and off to send information to your partner.

We can send any amount of data over wireless radio signals, but let’s start with a simple yes/no question. You can make something up: do you have lunch during 4th period, is there a test today, or anything at all. You can decide what yes and no mean. What did you come up with?

Now let’s ask a more interesting question: something with a number as an answer. You could ask what time it is, or or many people are in your class today, or something like that. What patterns did you use to represent “yes” and “no,” and how did they differ from the way you represented numbers?

Now try asking what time it is (the hours and the minutes) as one question. Things get trickier now, because you can send the number of hours, and then the number of minutes, but how will the other person know that you’ve switched from hours to minutes? Also, if it’s 11:59, that’s a lot of flashes of light, if you’re flashing one time to count each one. Is there a better way? Also, did you do anything to represent AM versus PM, and how could you handle that?

For one last challenge, switch to another group while they’re communicating, and see if you can come up with their right answer. You probably could not! If you join late, you don’t know where to start counting, or how much you missed. Is there a way you could communicate when you are starting and stopping each part of your message?

By blinking the light, you are introducing light at a certain frequency (or in the case of actual light, many frequencies). By blinking the light in a pattern, you’re modulating a signal onto that wave of light. This is how radio works. With amplitude modulation (AM) radio, you make the amplitude of the signal “louder” or “softer” to show changes in your signal. Frequency modulation (FM) changes the frequency of the signal: for example, if a radio station is broadcasting at 102.9 MHz in FM, it actually broadcasts between 102.8 and 103.0 MHz: if you “listen” to all of those together, you’ll see the signal move between those frequencies, higher and lower, as the signal changes. The top signal in the graph below shows a modulated FM signal (the middle signal is the actual signal being modulated, and the bottom signal is the original radio frequency). When the signal goes low, notice that the frequency at the top goes slightly below the original frequency, and as the signal goes up, the frequency goes slightly above the original frequency.

We are going to use Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM), so that we keep the flashlight on for a certain length of time to represent a digit or bit of information. For example, a quick flash might mean a 0, a long flash might mean a 1. What are some ways that you could tell time using PWM?

For example, you could send the hours and minutes one digit at a time. So, if it’s 9:58, you might send three signals: a 9, a 5, and an 8. Maybe the flashlight stays on for 1 second for each digit value. So you’d turn on the light for 9 seconds, then turn it off. Then, turn it on for 5 seconds, and then off, and then on for 8 seconds, and then off. This is a good start, but there are a few problems to work out:

- What happens if the number of hours has 2 digits in it, like 10:58?

- How do you handle AM versus PM?

- How long do you have to keep the light on so that the other person can see it? One second is a pretty long time, but what would happen if it was only one-tenth of a second per digit value?

- Was it hard to tell apart a 1 from a 9? How about a 7 from an 8? Are we trying to send too many different types of values? Could you come up with a solution that only sends a few types of values at a time, so you don’t have so much to tell apart?

WWVB

WWVB is a radio station operated by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) from Fort Collins, Colorado. It broadcasts the current time and date on a 60 kHz channel, which reaches most of the continental United States for use by clocks and watches to automatically set the time. This program reads and decodes 1000 Hz modulated audio according to the WWVB modulation standard.

This low frequency uses ground propagation to reach most of the country, and although best reception can be found during the overnight hours, it works remarkably well most days on the east coast as well. However, a properly tuned antenna would need to be some large proportion of the wavelength of the signal, and even a one-quarter wavelength antenna at this frequency would measure about 3 quarters of a mile in length! Because the WWVB signal consists of a slow and simple modulation strategy, its signal can be heard by devices with tiny inefficient antennas (small enough to fit in a wristwatch!).

This modulation strategy is called Pulse-Width Modulation. WWVB uses three kinds of data values that it sends using this modulation: a 0, a 1, and a marker bit. Sending a single bit takes one whole second, and during that second, a weak attenuated signal is sent followed by a stronger signal. The duration (or width) of that attenuated signal tells us what kind of bit we have. Here are the durations of each bit sent in a one second period:

| Bit | Attenuated Signal Width | Strong Signal Width |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 200 ms | 800 ms |

| 1 | 500 ms | 500 ms |

| Marker | 800 ms | 200 ms |

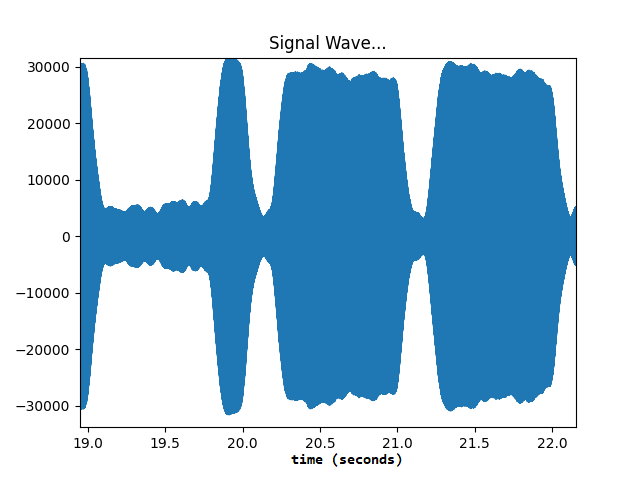

Here is an example signal that sends a marker bit followed by two zero bits. Notice that the first bit is quiet for almost one second (0.8 seconds), and then loud for the remainder of the second (0.2 seconds). That’s a marker. The second and third bits reverse that trend, and a requiet for only 0.2 seconds and then loud for the remainder of the second (0.8 seconds). These are zero bits. This signal transmitted a marker, followed by a 0, followed by a 0.

Here’s another example that sends a zero, a one, and a one bit.

If we listen carefully (or observe the strength of the radio signal), we can decipher the entire code. Over the course of one minute, WWVB will send 60 bit signals. Each one tells us something about the current time. Here’s what they mean:

| Bit | Meaning | Bit | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Marker | 30 | Add 8 to the day of the year |

| 1 | Add 40 to the number of minutes | 31 | Add 4 to the day of the year |

| 2 | Add 20 to the number of minutes | 32 | Add 2 to the day of the year |

| 3 | Add 10 to the number of minutes | 33 | Add 1 to the day of the year |

| 4 | Unused | 34 | Unused |

| 5 | Add 8 to the number of minutes | 35 | Unused |

| 6 | Add 4 to the number of minutes | 36 | DUT1 Time Correction + |

| 7 | Add 2 to the number of minutes | 37 | DUT1 Time Correction - |

| 8 | Add 1 to the number of minutes | 38 | DUT1 Time Correction + |

| 9 | Marker | 39 | Marker |

| 10 | Unused | 40 | DUT1 Time Correction of 0.8 seconds (add or subtract this from the current minute) |

| 11 | Unused | 41 | DUT1 Time Correction of 0.4 seconds |

| 12 | Add 20 to the number of hours (0 is midnight, 13 is 1 PM, 23 is 11 PM) |

42 | DUT1 Time Correction of 0.2 seconds |

| 13 | Add 10 to the number of hours | 43 | DUT1 Time Correction of 0.1 seconds |

| 14 | Unused | 44 | Unused |

| 15 | Add 8 to the number of hours | 45 | Add 80 to the 2-digit year (you need to know the current century!) |

| 16 | Add 4 to the number of hours | 46 | Add 40 to the 2-digit year |

| 17 | Add 2 to the number of hours | 47 | Add 20 to the 2-digit year |

| 18 | Add 1 to the number of hours | 48 | Add 10 to the 2-digit year |

| 19 | Marker | 49 | Marker |

| 20 | Unused | 50 | Add 8 to the 2-digit year |

| 21 | Unused | 51 | Add 4 to the 2-digit year |

| 22 | Add 200 to the number of days this year (1 is January 1) |

52 | Add 2 to the 2-digit year |

| 23 | Add 100 to the day of the year | 53 | Add 1 to the 2-digit year |

| 24 | Unused | 54 | Unused |

| 25 | Add 80 to the day of the year | 55 | Leap Year? |

| 26 | Add 40 to the day of the year | 56 | Leap Second? |

| 27 | Add 20 to the day of the year | 57 | Daylight Saving Time? (00 = standard time, 01 = DST ending, 02 = DST beginning, 03 = DST) |

| 28 | Add 10 to the day of the year | 58 | Daylight Saving Time? |

| 29 | Marker | 59 | Marker |

You could tune in and listen to the signal, and you’d hear something like this (warning - beeping sounds!):

The tone is modulated onto the 60 kHz signal at 1000 Hz, and you can hear it get weaker and stronger each second. In theory, an attentive human with a sharp ear could listen and figure out the current time (or at least the time exactly one minute ago). If you did, I believe you would hear that this audio sample was broadcast at 2:47 AM Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) on February 1, 2009. In practice, we use circuits and programming to decode the signal automatically.

Running the Programs

Youtube Decoder

The wwvb-youtube-decoder.py program downloads the audio from this WWVB sample. It is run via:

python wwvb-youtube-decoder.py

and will print out the current time and date as of the time of that recording. My program decodes this audio sample as 2:47 AM Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) on February 1, 2009.

WAV Decoder

If you have your own audio file sample of WWVB already, you can run:

python wwvb-wav-decoder.py <input.wav>

to decode its audio and print the associated time and date.

WWVB Audio Simulator

If you can’t record the WWVB signal yourself, you can use this program to generate a one-minute WAV file simulating the WWVB signal for the current time and date. You can then run the WAV Decoder to decode this audio.

python wwvb-generator.py

This will generate a file called output.wav by default, that sounds like this one (warning: beeping sounds!):

This particular sample is the one that is decoded by running the replit below. This sample was generated on July 12, 2022, at 9:13 AM. If you run the replit, it should display this date and time! If you run the wwvb-generator.py script, it will generate a new output.wav file with the current date and time, which you can upload to this replit and decode again (it should print the date and time that you created this new sample!

One note is that the time is in the Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) time zone, so that it is the same time zone for everyone around the world. The time you get may differ by a few hours or parts of an hour, depending on the time zone you are in. That’s normal! For example, Eastern Standard Time is 5 hours earlier than UTC, or 4 hours earlier during Daylight Saving Time.

WAV Plotter

If you’d like to generate the waveforms shown above, you can run the WAV Plotter on a given audio sample:

python wavplot.py <input.wav>

How it Works

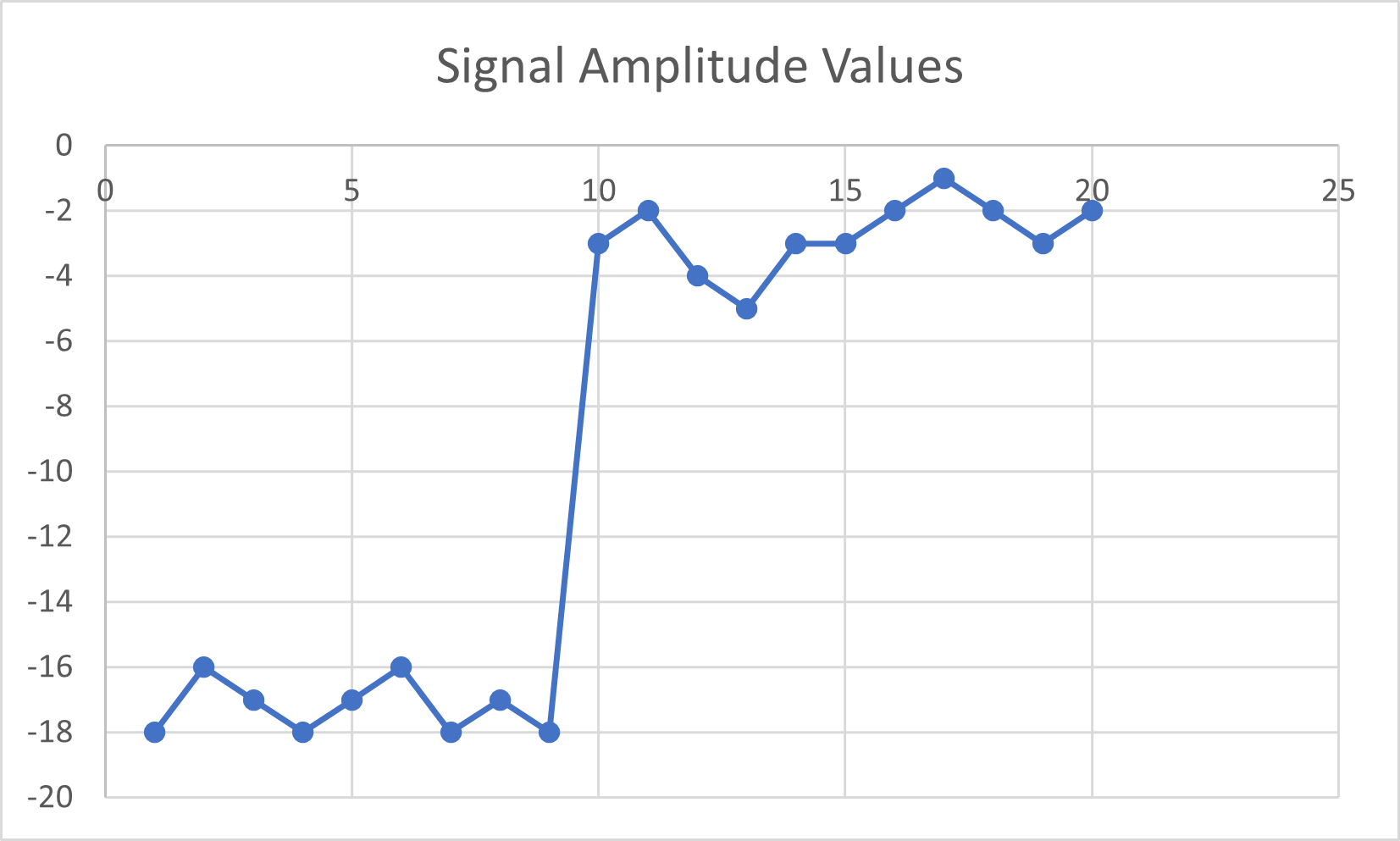

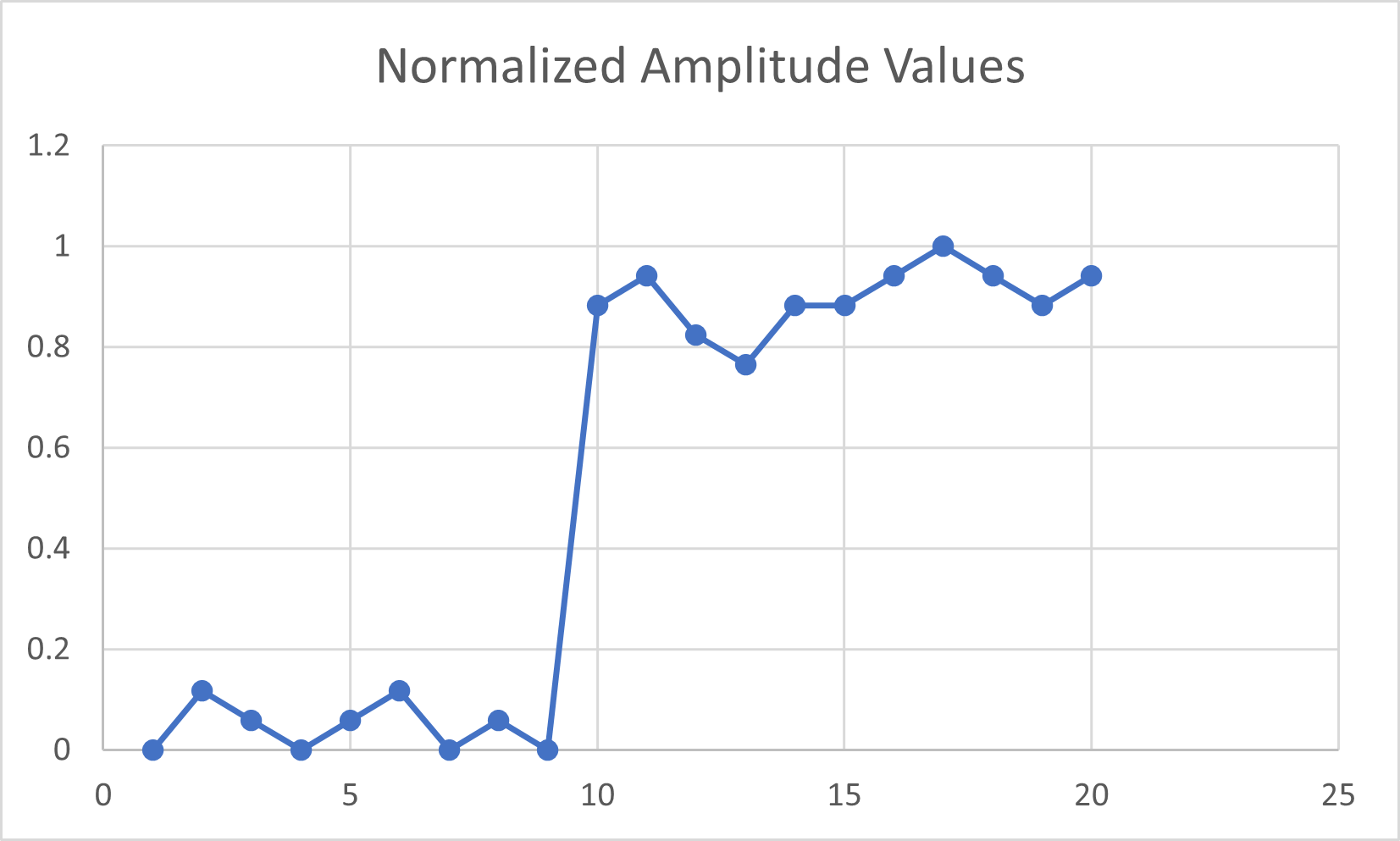

Our program doesn’t actually “listen” to the audio like a human does, but it does something really similar! The computer looks at the audio waves of the file, which “wiggle” at different frequencies to produce the sounds that you hear in your ear. We know that WWVB encodes a 1000 Hz tone onto the signal, so that’s the frequency we’ll listen for. We also know that the amplitude of this signal will change over time (getting louder and softer). There is a mathematical function called the Fourier Transform that can tell us the amplitude of a signal (like a sound) at a certain frequency. That’s exactly what we want to know! So, we break up the one minute audio file into small pieces, and asked the amplitude of the 1000 Hz tone at that time. I made the pieces 0.05 seconds apart: there’s no one right answer here, but I thought 0.05 seconds was a good choice because we know that WWVB changes its amplitude at 0.2 seconds, 0.5 seconds, and 0.8 seconds. 0.05 seconds was smaller than all of those, but still big enough to get a good enough sample of the audio to run the Fourier Transform with. I called this the get_amplitudes function in the wwvbhelper.py file.

In a given second, I should have a collection of 20 of these amplitude samples (1 second / 0.05 seconds = 20 “windows”). The first few amplitudes should be low, and the remaining ones will be high. How many are low and high is the question, since that will tell us if we have a 0 bit, a 1 bit, or a marker. One challenge is that we don’t know exactly how strong the signal will be, so we can’t look for a specific number. Even though we know how strong of a signal WWVB transmits from Fort Collins, Colorado, that signal can be made weaker by the weather, environmental factors, and how far away we are from the station. We just know that it will start weaker and get stronger. Even still, there are lots of ways to do this. I wrote a function identify_bit in wwvbhelper.py to try this out.

My approach to identifying a bit within those 20 amplitude samples is to “normalize” the amplitude values themselves. That way, if the amplitudes start at -8 dB and go to -2 dB, or if they start at 1 dB and go to 5 dB, etc., my amplitude values will always be on a scale between 0 and 1. This is a little bit like averaging your test scores in a class so that they’re all out of 100 points. To normalize the values, I took each value and replaced it with itself minus the smallest amplitude in the sample, and divided that by the maximum value minus the minimum value (the range), as you can see in the formula below:

\(x_{i} = \frac{x_{i} - min(x)}{max(x) - min(x)}\)

So we’re left with a measurement of the distance of each value from its smallest, divided by its range (to make the scale 0 through 1). In Python, we can scale an entire array in one line of code using the numpy (np) library:

wnd = (wnd - np.min(wnd)) / (np.max(wnd) - np.min(wnd))

Here are the values before normalizing and after.

| Signal Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original (Denormalized) Value | -18 | -16 | -17 | -18 | -17 |

| Normalized Value | 0 | 0.117647 | 0.058824 | 0 | 0.058824 |

| Signal Number | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Original (Denormalized) Value | -16 | -18 | -17 | -18 | -3 |

| Normalized Value | 0.117647 | 0 | 0.058824 | 0 | 0.882353 |

| Signal Number | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Original (Denormalized) Value | -2 | -4 | -5 | -3 | -3 |

| Normalized Value | 0.941176 | 0.823529 | 0.764706 | 0.882353 | 0.882353 |

| Signal Number | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Original (Denormalized) Value | -2 | -1 | -2 | -3 | -2 |

| Normalized Value | 0.941176 | 1 | 0.941176 | 0.882353 | 0.941176 |

They look different, but take a closer look below:

They’re exactly the same, except that we changed the scale from 0 to 1! Now we don’t have to worry about the original raw values.

Now, I count how many values are small before they become large. The identify_bit in wwvbhelper.py function loops over the array of 20 normalized amplitudes, and finds the spot in the middle where the values start going over 0.5. I ignore the first time I see this, just in case there’s some noise, but I think it would have worked the same way without this. Since each amplitude is worth 0.05 seconds of data, I multiply this spot by 0.05, and that’s how many seconds it took.

To convert this into a 0, 1, or 2, I look at this time. We know that a transition at 0.2 seconds is a 0, a transition at 0.5 seconds is a 1, and a transition at 0.8 seconds is a marker, but the signal could be noisy. I’ll split the difference and call a marker anything below 0.35 seconds, a 1 anything below 0.65 seconds, and everything above 0.65 seconds a marker. I do this 60 times, one for each second, and generate an array of bit values (0, 1, and 2 for marker).

The decode function in wwvbhelper.py takes this collection of 60 bits, and calculates the current time. For example, the first bit should always be a marker, and the second bit starts to tell us how many minutes number of minutes are in the current time. If the second bit is a 1, there are at least 40 minutes in the current time. The third bit tells us if there are 20 more minutes, and so on. We can check if they are 1 values, and add up the number of minutes. Rince and repeat for hours and days, and you’ve got the time!

Finally, there is one last challenge to consider. The message takes one minute to transmit, and it starts right at the start of each minute on the clock. Thinking about the flashlight example, what would happen if you joined late? You could wait until the next signal began, but when will that be? Even if you know it’s at the start of a minute, you don’t actually know what time it is (or else you wouldn’t need to listen to the signal!). This is the purpose of the marker bits. If you look at the WWVB timing diagram, you’ll see that a marker is the first bit, so that is helpful. But there are other markers in the message! How can you know that the marker is telling you that the message is starting (as a hint, look at the end of the message and see what plays right before the starting marker as the prior message ends).

Follow-Up

What would happen to our signal and our program if a bolt of lightning struck while we were listening to the audio, or some other noise entered into the signal itself? What would happen if we lost reception for a few seconds? What do you think we could do about that (and what should we do about that)?

Could you modify this program to send a different kind of message? Perhaps a text message? What would you have to change in the protocol? What would your message (symbol) rate be? How many symbols would you send, and how long would it take you to represent each one? What’s the drawback to having more symbols?

Notice that WWVB modulates its signal at 1000 Hz. Could it be posssible to encode additional information using different frequencies? How might you send more types of information (“symbols”) in your message, beyond the 0, 1, and marker symbols we saw earlier? How might this make decoding more difficult?

The Finished Project

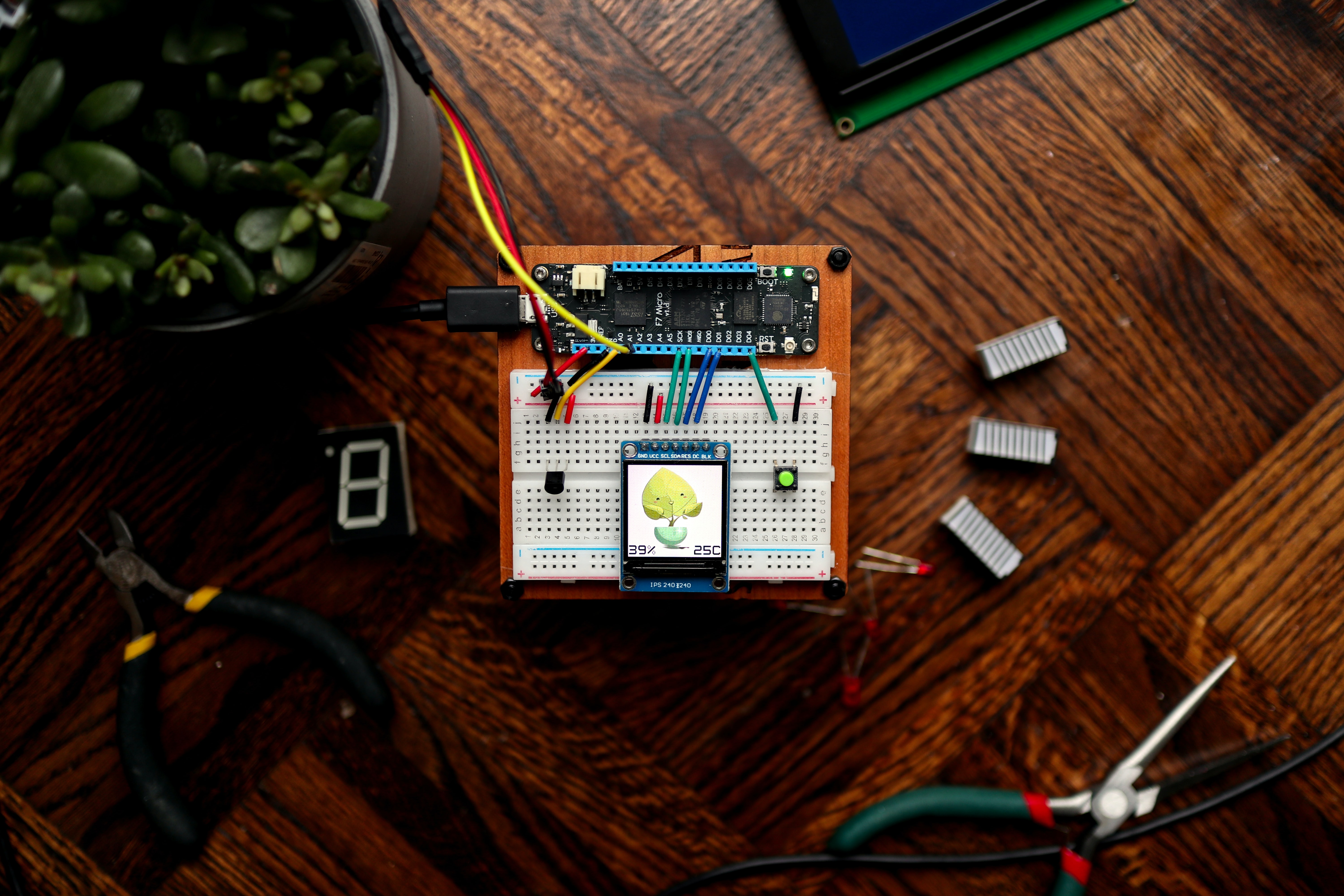

Here’s my finished product for the WWVB decoder, available at https://replit.com/@BillJr99/WWVB-Decoder:

The complete source code for all the programs is available at https://www.github.com/BillJr99/WWVB/.