Zero Knowledge Coin Flipping

Secondary Computing (Microbit)

In this activity, we will learn about zero knowledge protocols to exchange secret information over the Internet.

Activity

A Motivating Problem: Flipping a Coin

Suppose you wanted to flip a coin and have the other person guess. If they guess correctly, they get to go first at a game, or win some prize, so there is some incentive for both players to cheat. If you don’t have a coin sitting around, here’s a button that will simulate one:

Worse yet, you might be flipping the coin and talking over the phone, or sending chat messages over the Internet, so you can’t actually see each other. How can you flip the coin in a way that you know both people are playing fairly?

Zero Knowledge

A mathematical construct known as Zero Knowlege Proofs give us a way to let the other person know that we know whether the coin was heads or tails, without actually revealing it. In other words, we can share a way for the other person to verify the coin toss once we tell them, but without actually telling them what it is. Later, when we reveal whether the coin toss was heads or tails, they can use the earlier information to verify that we were telling the truth. The mathematics of this are related to modern cryptographic protocols that we use to encrypt information on the Internet. We won’t do that math today, but we will demonstrate the functionality that this math provides.

Providing One-Way Verification Information

The key to these Zero Knowledge protocols is providing some information that would reveal the answer, but in a way that cannot be reverse-engineered into the answer directly. So, the other person knows that we know the answer, but doesn’t gain any information about the answer (other than that we know what it is).

For example, suppose you were playing Where’s Waldo. This is a puzzle where you are searching for a character on a page full of pictures, like a seek-and-find. You want to show someone that you’ve solved it, but don’t want to spoil it for them. One way you could do this is by cutting out a circle to outline Waldo, and holding it over the page, so that the other person can see Waldo behind it, without seeing any part of the page or book.

Another classic example is the Zero Knowledge Cave. Here, there are two paths through a cave, both leading back to the entrance, but the path is blocked in the middle. If you wanted to prove that you can get through the locked door or obstacle in the way, someone could watch you enter the cave on one path, and then return through the other. As long as they don’t follow you, they don’t know how you managed to get through it, but they can be pretty sure that you did.

Zero Knowledge and the Coin Toss

Returning to the coin toss, suppose we flip the coin and see that it is Heads. We don’t want to tell the other person this, because they might cheat and guess Heads now that they know the answer. But they don’t want to tell us the answer, either, for the same reason!

Instead, we provide some verification information that will prove that we know (and did not change) the coin toss result. To do this, we’ll look in a phone book (here is one and here is another), and choose the name of a person that begins with the letter H (for Heads). We’ll share their phone number.

The other person would have a very difficult time searching for that phone number in the phone book. It is theoretically possible, but very unlikely (and unlikely to work more than once!). This is an example of a one way hash function. Knowing a person’s name, we can look up the phone number easily, but it is very difficult to reverse this search by phone number to get a name.

Now, the other person gives their guess, and we can reveal that the coin toss was indeed Heads. We do this by revealing the name associated with the phone number, and allowing the other person to verify that their name begins with the letter H!

Building the Phone Book Mini Zero Knowledge Protocol

Using the micro:bit, we can write a program to “flip a coin” (we could use a random number generator for this, but I decided to:

- Allow the user to pick heads or tails using the buttons!)

- Send a phone number associated with a name beginning with that letter

- Allow the other user to guess heads or tails

- Send the name associated with that phone number and determine the winner

on start

We’ll use the Bluetooth radio to send this information back and forth between two radios. We’ll set the radio group to 1 (although other groups should change this number to something unique so that they only hear each other), and set three variables:

- player is the player number, 0 or 1. 0 will flip the coin, and 1 will guess

- heads_tails is 0 if the coin flip is heads, and 1 if it is tails

- guess similarly, the other person’s guess is 0 for heads, and 1 for tails

Just because, I send a placeholder radio message in on start. This is optional, but causes the simulator to load the second radio for simulation.

on button A+B pressed

In each group, there will be one player 1 (flipping the coin) and one player 2 (guessing). When the A+B buttons are pressed together, we’ll set player to player plus 1, and then take the remainder divided by 2. So, if player was 0, it will become 1, and if it is 1, it will become 0 (2 divided by 2 leaves no remainder).

I show the player number on the screen, and set a few more variables. You could set these in on start too, but I happened to set them here.

- hintsent and guesssent represent whether we have exchanged information yet. At this point, we have not, so set these to 0.

- tailsnumber and tailsname: this is a phone number and name from a phone book of a person with a name beginning with the letter T for Tails.

- headsnumber and headsname: same as above, but with the letter H for Heads.

on button A pressed

From here, the behavior of the program depends on whether you’re player 1 or player 2. So we’ll use logic if statements to check on this. If the player number is 0, we’ll flip heads_tails between 0 and 1, just like we did with player above.

Then, if heads_tails is 0, we’l set phonenumber and phonename to headsnumber and headsname. Otherwise, we’ll set them to tailsnumber and tailsname.

If player is 1, set guess to 0 or 1 just like you did with heads_tails.

For fun, I show an icon on the screen if guess or heads_tails is 0 or 1. I used a heart for Heads and a musical note for Tails, so that the player knows what they’ve guessed or flipped.

on button B pressed

Player 0 should send the hint to the other player. We don’t want to tell them the answer, just the hashed value. So, we’ll send the phone number. Send a radio string message. It’s important that we send things in a consistent way so they can be unpacked by the ohter player, so I joined the strings num : and phonenumber. The : character gives us a way to see what kind of message we just received on the left of the :, and unpack the data to the right. We’ll set hintsent to 1 as well now that we’ve sent the hint.

Player 1 should send a radio number guess, and set guesshint to 1. You could send a string here and send a phone number as well, but since we wouldn’t send this information without already knowing the hashed hint, we can feel safe that the other player has committed to their coin flip, so there’s nothing lost in sharing this with them. Sometimes, however, both parties have secrets, and so there’s nothing stopping us from doing the same thing in reverse! To keep things simple, we’ll just send the value here.

checking for a winner

Because both players have to check for a winner, I made a function here to do that. This way, I don’t have to copy this logic all over the place. It checks if guess is equal to heads_tails and, if so, shows an icon (I used a checkmark). Otherwise, it shows a different icon (I used an X). To ensure these icons stay on the screen long enough to see, I put a pause for 1 second here as well. I called this function checkForWinner.

Receiving the Messages

Now, all that remains is what to do when we receive a number or string from the B button press above.

on radio received (number)

When we receive a number, it must be the guess from the non-flipping player 1. So, if player is 0, we can set guess to the received number, and set guesssent to 1. At this point, we can check for a winner, reveal the answer, and reveal the name that goes with the phone number. We know this because we wouldn’t receive a guess until the other player received the hashed hint (the phone number).

So, we’ll send a number (heads_tails) representing the actual coin flip, because it is safe to do so now. We’ll also send a String containing the joined strings name : phonename. Really, this is all we need to send, and we can skip sending heads_tails, because we know for sure that it would have to match. But, for fun, since we were trying to flip a coin, we’ll send both pieces of information.

Now we can check for a winner, too. Call the checkForWinner function we just created.

Since we did just send a number back to player 1 (heads_tails), we can add an else statement right here for if we are player 1. If so, set heads_tails to the received number.

on radio received (String)

Player 1 is the only player to receive strings, so we don’t need an if statement checking the player number here, unless you’d like to add one to make things more readable.

Instead, we’ll check what the first word of the message is. There are two types of string messages we can received: one that starts with num and one that starts with name, depending on whether we’re receiving a phone number or the name of the person that goes with it.

From the Text menu, select the block called split(receivedString) at :. Place that block inside a get value at 0 block under the List menu. Put all of this in an if statement and check if this value is equal to num. If so, we’ll set phonenumber to the split of receivedString at : value at 1 (this is an identical block to the one you just made, except the 0 becomes a 1 to get the right hand side of the : character of the joined message).

Show phonenumber on the screen and set hintsent to 1.

Otherwise, we must be receiving a name message. Do the same thing, but set phonename to the received string value (at position 1, to get the right hand side of the : character). Show the phonename variable on the screen, and call checkForWinner, now that we know if there is a winner. We’ll have set the heads_tails variable already from the on radio received (number) block we just filled in, so this function is ready to work.

To Play

Player 0 and 1 should select their player number by pressing A+B at the same time. Then, press A to pick heads if you are player 0, or to guess if you are player 1. Player 0 presses B first to send the hint to player 1. Then, player 1 presses B to send their guess back to player 0. Player 0 automatically sends the result to player 1, and the results and phone name are shown on the screen.

Hash Functions

In practice, zero knowledge proofs use some number properties of mathematics including multiplying large prime numbers (for example, receiving a number that is the product of two large prime numbers, but not being able to factor that number quickly). This idea is also used in modern cryptographic functions. But the basic principle is that we share some information that is difficult to reverse. We can emulate our earlier use of a phone book with a one-way hash function.

This program works in a similar manner to the micro:bit program, except that we don’t have to look up phone numbers and names. Instead, we’ll enter our player number like before. Player 0 gives player 1 a message to hash (this could be a random string of words, or anything you like; this is to verify that they are flipping the coin right now in front of us - kind of like holding up a copy of today’s newspaper!). Player 1 decides if the coin toss is Heads or Tails, and creates a String consisting of the message we were asked to include, concatenated with Heads or Tails (or 1 or 0, or whatever encoding we are using). We don’t want to share this information yet, since it contains the answer, so instead, we’ll hash it with a one-way hash function:

hashed = hashlib.sha256(unhashed.encode("utf-8")).hexdigest()

The coin flipper shares this with the other player, who can now share their guess of heads or tails. Finally, the flipper sends the original string (the concatenation of the random message plus the coin toss result). The other player can see the result of the coin toss, and can hash this message themselves. The hash will match the hash that was given to them earlier, validating the result.

The program below can be run twice (once as the sender and once as the receiver):

Follow-Up

What secrets could you exchange this way besides flipping a coin? Modify this program to implement a protocol of your own design.

Also, if you recall, we sent a custom random string to be hashed along with the coin toss in the Python program. Why could we not just hash “Heads” or “Tails” by itself? How might this have been used for cheating if we had not included some random string (sometimes called a “salt” because it is a sort of seasoning infused into the data)?

The Finished Project

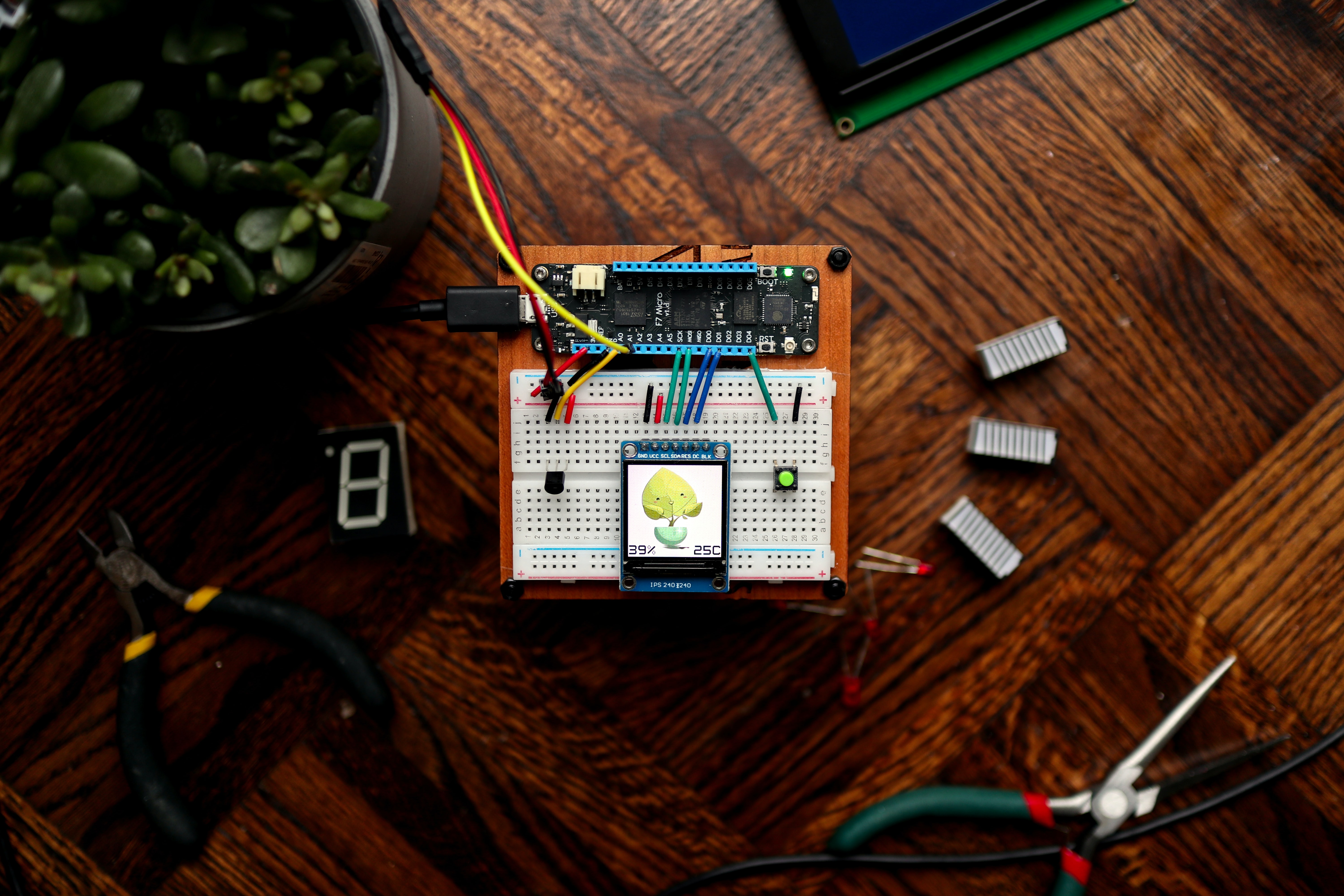

Here’s my finished product, available at https://www.billmongan.com/minizeroknowledgecoinflip/:

Here is the program for the hashing version of the Zero Knowledge Coin Flip, available at https://replit.com/@BillJr99/ZeroKnowledgeCoinFlip: